What Is The Most Recently Extinct Animal

Subfossil lemurs are lemurs from Madagascar that are represented by recent (subfossil) remains dating from nearly 26,000 years ago to approximately 560 years agone (from the late Pleistocene until the Holocene). They include both extant and extinct species, although the term more oftentimes refers to the extinct behemothic lemurs. The diverseness of subfossil lemur communities was greater than that of present-day lemur communities, ranging from as high as 20 or more species per location, compared with 10 to 12 species today. Extinct species are estimated to have ranged in size from slightly over ten kg (22 lb) to roughly 160 kg (350 lb). Even the subfossil remains of living species are larger and more robust than the skeletal remains of modernistic specimens. The subfossil sites constitute effectually about of the island demonstrate that most giant lemurs had wide distributions and that ranges of living species have contracted significantly since the inflow of humans.

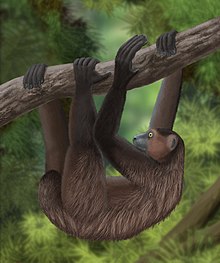

Despite their size, the giant lemurs shared many features with living lemurs, including rapid evolution, poor day vision, relatively pocket-size brains, and female person-dominated hierarchies. They also had many distinct traits amongst lemurs, including a tendency to rely on terrestrial locomotion, irksome climbing, and suspension instead of leaping, as well as a greater dependence on leaf-eating and seed predation. The giant lemurs probable filled ecological niches now left vacant, particularly seed dispersal for plants with large seeds. There were 3 distinct families of giant lemur, including the Palaeopropithecidae (sloth lemurs), Megaladapidae (koala lemurs), and Archaeolemuridae (monkey lemurs). Two other types were more closely related and similar in appearance to living lemurs: the giant aye-aye and Pachylemur, a genus of "giant ruffed lemurs".

Subfossil remains were start discovered on Madagascar in the 1860s, but giant lemur species were not formally described until the 1890s. The paleontological interest sparked by the initial discoveries resulted in an overabundance of new species names, the resource allotment of bones to the wrong species, and inaccurate reconstructions during the early on 20th century. Discoveries waned during the mid-20th century; paleontological work resumed in the 1980s and resulted in the discovery of new species and a new genus. Research has recently focused on diets, lifestyle, social behavior, and other aspects of biology. The remains of the subfossil lemurs are relatively recent, with all or most species dating within the last 2,000 years. Humans first arrived on Madagascar around that fourth dimension and hunting likely played a role in the rapid decline of the lemurs and the other megafauna that once existed on the large island. Additional factors are thought to accept contributed to their ultimate disappearance. Oral traditions and recent reports of sightings by Malagasy villagers have been interpreted by some as suggesting either lingering populations or very recent extinctions.

Diverseness [edit]

Extinct giant lemurs [edit]

Until recently, behemothic lemurs existed in Republic of madagascar. Although they are only represented past subfossil remains, they were modern forms, having adaptations dissimilar those seen in lemurs today, and are counted as role of the rich lemur diversity that has evolved in isolation for upward to 60 1000000 years.[1] All 17 extinct lemurs were larger than the extant forms, including the largest living lemurs, the indri (Indri indri) and diademed sifaka (Propithecus diadema), which weigh up to 9.5 kg (21 lb).[ii] The estimated weights for the subfossil lemurs have varied. Techniques used for these weight estimations include the comparing of skull lengths, tooth size, the head diameter of the femur, and more recently, the surface area of cortical os (hard os) in long basic (such as the humerus).[3] Despite the variations in the size estimates for some species, all subfossil lemurs were larger than living species, weighing ten kg (22 lb) or more, and one species may take weighed every bit much every bit 160 kg (350 lb).[iv]

All simply i species, the giant aye-yeah, are thought to have been active during the day.[5] Not just were they unlike the living lemurs in both size and appearance, they besides filled ecological niches that no longer exist or are now left unoccupied.[i] Their remains have been plant in most parts of the island, except for the eastern rainforests and the Sambirano domain (seasonal moist forests in the northwest of the island), where no subfossil sites are known.[6] Radiocarbon dates for subfossil lemur remains range from approximately 26,000 years BP (for Megaladapis in northern Madagascar at the Ankarana Massif) to around 500 years BP (for Palaeopropithecus in the southwest).[6] [7]

Characteristics [edit]

All of the extinct subfossil lemurs, including the smallest species (Pachylemur, Mesopropithecus, and the giant aye-aye), were larger than the lemur species live today. The largest species were amidst the largest primates ever to accept evolved. Due to their larger size, the extinct subfossil lemurs accept been compared to big-bodied anthropoids (monkeys and apes), however they more closely resemble the minor-bodied lemurs.[eight] Similar other lemurs, the subfossil lemurs did not exhibit appreciable differences in body or canine tooth size betwixt males and females (sexual dimorphism).[8] This suggests that they, too, exhibited female person social potency, perchance exhibiting the same levels of agonism (aggressive competition) seen in extant lemurs. Similar other lemurs, they had smaller brains than comparably sized anthropoids. Most species also had a unique strepsirrhine dental trait, chosen a toothcomb, which is used for grooming. Fifty-fifty tooth development and weaning was rapid compared to similarly sized anthropoids,[8] suggesting faster sexual maturity of their offspring.[8] Virtually subfossil lemurs also had loftier retinal summation (sensitivity to depression calorie-free), resulting in poor mean solar day vision (depression visual vigil) compared to anthropoids.[8] This has been demonstrated by the ratio betwixt their relatively pocket-size orbits (eye sockets) and the relative size of their optic canal, which is comparable to that of other lemurs, non diurnal anthropoids.

These traits are shared amidst both living and extinct lemurs, simply are uncommon among primates in full general. Ii prevailing hypotheses to explicate these unique adaptations are the energy frugality hypothesis by Patricia Wright (1999) and the evolutionary disequilibrium hypothesis past Carel van Schaik and Peter K. Kappeler (1996). The energy frugality hypothesis expanded on Alison Jolly's free energy conservation hypotheses by claiming that most lemur traits not only help conserve energy, but besides maximize the utilise of highly limited resources, enabling them to alive in severely seasonal environments with low productivity. The evolutionary disequilibrium hypothesis postulated that living lemurs are in the process of evolving to fill open up ecological niches left by the recently extinct subfossil lemurs. For example, small nocturnal prosimians are typically nocturnal and monogamous, while the larger living lemurs are generally active both day and dark (cathemeral) and live in modest groups (gregarious). Cathemerality and increased gregariousness might indicate that the larger living lemurs are evolving to fill the function of the giant lemurs, which were thought to exist diurnal (day-living) and more monkey-like in beliefs. Since virtually giant subfossil lemurs have been shown to share many of the unique traits of their living counterparts, and not those of monkeys, Godfrey et al. (2003) argued that the free energy frugality hypothesis seems to best explain both living and extinct lemur adaptations.

The skull and teeth of Pachylemur insignis advise that it ate more often than not fruit and some leaves.

Despite the similarities, subfossil lemurs had several distinct differences from their lemur relatives. In add-on to beingness larger, the subfossil lemurs were more dependent on leaves and seeds in their diet, rather than fruit. They utilized deadening climbing, hanging, and terrestrial quadrupedalism for locomotion, rather than vertical clinging and leaping and arboreal quadrupedalism. Also, all simply one of them—the giant yep-aye—are assumed to have been diurnal (due to their body size and modest orbits), whereas many modest lemurs are nocturnal and medium-sized are cathemeral.[6]

Their skeletons suggest that most subfossil lemurs were tree-dwellers, adapted for living in forests and maybe express to such habitats.[vi] [8] Unlike some of the living species, the subfossil lemurs lacked adaptations for leaping. Instead, suspension, used past some indriids and ruffed lemurs, was extensively used in some lineages. Living lemurs are known to visit the ground to varying extents, merely only the extinct archaeolemurids exhibit adaptations for semiterrestrial locomotion. Due to the size of the extinct subfossil lemurs, all were likely to travel on the ground between trees.[8] They had shorter, more robust limbs, heavily built centric skeletons (trunks), and big heads[ten] and are idea to have shared the common lemur trait of depression basal metabolic rates, making them slow-moving. Studies of their semicircular canals ostend this assumption, showing that koala lemurs moved slower than orangutans, monkey lemurs were less active than Old World monkeys, and sloth lemurs exhibited slow movements like those of lorises and sloths.[eleven]

Types [edit]

Archaeoindris was the largest of the sloth lemurs, and the largest known lemur. It weighed approximately 160 kg (350 lb).

- Sloth lemurs

The sloth lemurs (family Palaeopropithecidae) were the about species-rich group of the subfossil lemurs, with four genera and viii species. The common name is due to strong similarities in morphology with arboreal sloths, or in the instance of Archaeoindris, with giant basis sloths.[12] They ranged in size from some of the smallest of the subfossil lemurs, such as Mesopropithecus, weighing equally little as x kg (22 lb),[12] to the largest, Archaeoindris, weighing approximately 160 kg (350 lb).[iv] Their characteristic curved finger and toe bones (phalanges) propose dull suspensory move, similar to that of an orangutan or a loris, making them some of the well-nigh specialized mammals for suspension.[13] Their day vision was very poor, and they had relatively small-scale brains and short tails.[8] Their diet consisted mostly of leaves, seeds, and fruit;[eight] dental clothing analysis suggests they were primarily folivorous seed-predators.[14]

- Koala lemurs

The koala lemurs of the family Megaladapidae most closely resemble marsupial koalas from Commonwealth of australia. According to genetic evidence they were near closely related to the family Lemuridae, although for many years they were paired with the sportive lemurs of the family Lepilemuridae due to similarities in their skulls and tooth teeth.[12] They were slow climbers and had long forelimbs and powerful grasping feet, possibly using them for suspension.[viii] [12] Koala lemurs ranged in size from an estimated 45 to 85 kg (99 to 187 lb),[12] making them as large as a male orangutan or a female person gorilla. They had poor day vision, short tails, lacked permanent upper incisors, and had a reduced toothcomb.[8] Their diet generally consisted of leaves,[8] with some species being specialized folivores and others having a broader diet, maybe including tough seeds.[14]

Monkey lemurs, such equally Hadropithecus stenognathus (above) and Archaeolemur edwardsi (below), were the nearly terrestrial of the lemurs.

- Monkey lemurs

Monkey lemurs, or baboon lemurs, share similarities with macaques; they have also been compared to baboons.[fifteen] Members of the family Archaeolemuridae, they were the most terrestrial of the lemurs,[12] with short, robust forelimbs and relatively flat digits. They spent time on the ground, and were semi-terrestrial, spending fourth dimension in trees to feed and sleep. They were heavy-bodied and ranged in size from approximately 13 to 35 kg (29 to 77 lb).[8] [12] They had relatively skillful day vision and big brains compared with other lemurs.[8] Their robust jaws and specialized teeth suggest a diet of hard objects, such equally nuts and seeds, yet other evidence, including fecal pellets, suggests they may have had a more varied diet, including leaves, fruit, and animal matter (omnivory).[8] [12] Dental wear analysis has shed some light on this dietary mystery, suggesting that monkey lemurs had a more than eclectic diet, while using tough seeds as a fall-back food item.[fourteen] Inside the family, the genus Archaeolemur was the most widespread in distribution, resulting in hundreds of subfossil specimens, and may have been 1 of the final subfossil lemurs to dice out.[sixteen]

- Giant yep-aye

An extinct, giant relative of the living yeah-yep, the behemothic aye-aye shared at least two of the aye-aye's baroque traits: ever-growing key incisors and an elongated, skinny eye finger.[8] These shared features suggest a similar lifestyle and diet, focused on percussive foraging (tapping with the skinny digit and listening for reverberation from hollow spots) of defended resources, such as hard basics and invertebrate larvae curtained inside decaying wood. Weighing every bit much as 14 kg (31 lb), it was between two-and-half and five times the size of living yep-aye.[seven] [12] Alive when humans came to Republic of madagascar, its teeth were collected and drilled to make necklaces.

- Pachylemur

The simply extinct member of the family Lemuridae, the genus Pachylemur contains 2 species that closely resembled living ruffed lemurs. Sometimes referred to as "giant ruffed lemurs", they were approximately 3 times larger than ruffed lemurs, weighing between 10 and 13 kg (22 and 29 lb).[12] Despite their size, they were arboreal quadrupeds, mayhap utilizing more suspensory beliefs and cautious climbing than their sister taxon.[7] [12] [15] Their skull and teeth were similar to those of ruffed lemurs, suggesting a nutrition high in fruit and possibly some leaves. The residual of its skeleton (postcrania) was much more robust and their vertebrae had distinctly different features.[8]

Phylogeny [edit]

Determining the phylogeny of subfossil lemurs has been problematic because studies of morphology, developmental biology, and molecular phylogenetics have sometimes yielded conflicting results. All studies agree that the family unit Daubentoniidae (including the giant aye-aye) diverged outset from the other lemurs at to the lowest degree 60 million years ago. The human relationship between the remaining families has been less clear. Morphological, developmental, and molecular studies have offered support for lumping the four sloth lemur genera of the family Palaeopropithecidae with the family Indriidae (including the indri, sifakas, and woolly lemurs).[17] The placement of family unit Megaladapidae has been more controversial, with similarities in teeth and skull features suggesting a shut human relationship with family Lepilemuridae (sportive lemurs).[17] [viii] Molecular data, instead, betoken a closer relationship to family unit Lemuridae.[17] Likewise, a relationship between family unit Archaeolemuridae and family unit Lemuridae has been suggested, based on morphological and developmental traits, yet molar morphology, the number of teeth in the specialized toothcomb, and molecular analysis back up a closer relationship with the indriid–sloth lemur clade.[17] Other subfossil lemurs, including the behemothic yeah-yep and Pachylemur, are more easily placed due to stiff similarities with existing lemurs (the aye-yeah and ruffed lemurs, respectively).[8]

| Subfossil lemur phylogeny[8] [eighteen] [19] |

Living species [edit]

Subfossil remains of the indri (Indri indri) suggest a meaning recent reduction in its geographic range.

Subfossil sites in Republic of madagascar have yielded the remains of more simply extinct lemurs. Extant lemur remains have also been found, and radiocarbon dating has demonstrated that both types of lemur lived at the same time. In some cases living species are locally extinct for the expanse in which their subfossil remains were institute. Because subfossil sites are found across nearly of the island, with the most notable exception existence the eastern rainforest, both paleocommunity composition and paleodistributions can be determined. Geographic ranges have contracted for numerous species, including the indri, greater bamboo lemur, and ruffed lemurs.[6] For instance, subfossil remains of the indri accept been found in marsh deposits near Ampasambazimba in the Central Highlands[xx] and in other deposits in both central and northern Madagascar, demonstrating a much larger range than the small region on the east coast that it currently occupies.[6] Even the greater bamboo lemur, a critically endangered species restricted to a pocket-sized portion of the southward-fundamental eastern rainforest, has undergone significant range contraction since the mid-Holocene,[6] [21] with subfossil remains from Ankarana Massif in the far due north of Madagascar dating to 2565 BCE ± 70 years.[22] Combined with finds from other subfossil sites, data suggests that it used to range beyond the northern, northwestern, central, and eastern parts of the isle.[vi] [21] Information technology is unclear whether these locations were wetter in the past or whether distinct subpopulations or subspecies occupied the drier forests, much like modern diversity of sifakas.[6] [20]

In addition to previously having expanded geographic ranges, extant subfossil lemurs exhibited meaning variation in size.[23] Researchers accept noted that subfossil bones of living species are more robust and by and large larger than their present-day counterparts.[twenty] The relative size of living species may be related to regional ecological factors, such as resources seasonality, a trend that is nevertheless observable today, where individuals from the spiny forests are, on average, smaller than individuals from the southwestern succulent woodlands or the dry deciduous forests.[23]

Environmental [edit]

Every bit a group, the lemurs of Republic of madagascar are extremely diverse, having evolved in isolation and radiated over the past 40 to 60 meg years to fill many ecological niches normally occupied by other primates.[1] In the contempo past, their diverseness was significantly greater, with 17 extinct species[17] sharing body proportions and specializations with lorises and various non-primates, such as tree sloths, giant ground sloths, koalas, and striped possums (genus Dactylopsila).[vi] [24] The variety of lemur communities today can exist as high as 10 to 12 species per region; communities of 20 or more lemur species existed as recently as 1,000 years ago in areas that at present have no lemurs at all.[6] [8] Only like living species, many of the extinct species shared overlapping ranges with closely related species (sympatry) through niche differentiation (resource partitioning).[half-dozen] [8] Amongst all the late Quaternary assemblages of megafauna, but Madagascar was dominated past large primates.[17]

Although anatomical prove suggests that even the big, extinct species were adapted to tree-climbing, some habitats, including gallery forests and the spiny forests of southern Republic of madagascar, in which they occurred would not have allowed them to be strictly arboreal. Even today, most lemur species will visit the ground to cross open areas, suggesting that the extinct species did the aforementioned. Monkey lemurs (family Archaeolemuridae), including Archaeolemur majori and Hadropithecus stenognathus, accept been reconstructed as being primarily terrestrial.[25] In contrast, the sloth lemurs (family unit Palaeopropithecidae) were highly arboreal despite the large size of some species.[26]

Species of both extinct and living (extant) lemur vary in size based on habitat conditions, despite their differences in niche preference. Within related groups, larger species tend to inhabit wetter, more than productive habitats, while smaller sister taxa are establish in drier, less productive habitats. This pattern suggests that populations of both living and extinct lemur species had become geographically isolated by differences in habitat and evolved in isolation due to varying principal production within different ecosystems. Thermoregulation may also have played a office in the evolution of their increased trunk size.[27] Nevertheless despite this pressure level to specialize and differentiate, some of the extinct subfossil lemurs, such equally Archaeolemur, may have had isle-broad distributions during the Holocene, unlike the living lemurs. If this is the case, it may suggest that some larger lemurs might have been more tolerant to regional differences in ecology than living lemurs.[six]

Diet [edit]

Inquiry on subfossil lemur diets, particularly in southern and southwestern Republic of madagascar, has indicated that ecological communities have been significantly affected by their recent extinction.[25] Many extinct subfossil lemurs were large-bodied leaf-eaters (folivores), seed predators, or both. Today, leaf-eating along with seed predation is simply seen in mid-sized lemurs, and is far less mutual than it was in the past. Strict folivory is also less common, at present establish primarily in small lemurs.[eight] In certain cases, subfossil lemurs, such as the sloth lemurs and koala lemurs, may have used leaves as an important fallback food, whereas other species, such as the monkey lemurs and the behemothic yeah-yep, specialized on structurally defended resource, such equally hard seeds and woods-irksome insect larvae. Last, Pachylemur was primarily a fruit eater (frugivorous). Subfossil lemur diets have been reconstructed using analytical tools, including techniques to compare tooth anatomy, structure, and wear; biogeochemistry (analysis of isotope levels, like carbon-13); and the dissection of fecal pellets associated with subfossil remains.[eight] [25]

The diets of near subfossil lemurs, about notably Palaeopropithecus and Megaladapis, consisted primarily of C3 plants, which use a class of photosynthesis that results in higher h2o loss through transpiration. Other subfossil lemurs, such as Hadropithecus and Mesopropithecus, fed on CAM and Cfour plants, which use more water-efficient forms of photosynthesis. Fruit and brute thing was more common in the diets of subfossil lemurs including Pachylemur, Archaeolemur, and the behemothic yes-aye. In southern and southwestern Madagascar, the subfossil lemurs of the spiny forests generally favored the C3 plants over the more than abundant CAM plants, although closely related sympatric species may have fed upon the two types of plants in unlike ratios, allowing each to divide resources and coexist. Since plants produce defenses confronting leaf-eating animals, the all-encompassing use of spines past plants in the spiny forests suggest that they evolved to cope with leaf-eating lemurs, big and small.[25]

Seed dispersal [edit]

Giant subfossil lemurs are idea to have also played a pregnant part in seed dispersal, mayhap targeting species that did not attract the seed dispersal services of the extinct elephant birds. Biogeochemistry studies take shown that they may take been the primary seed dispersers for the endemic and native C3 trees in the spiny forests. Terrestrial species may take dispersed seeds for small bushes as well as tall trees. Seed dispersal tin can involve passing seeds through the gut (endozoochory) or attaching the seeds to the animal's body (epizoochory), and both processes probably occurred with subfossil lemurs. Seeds from Uncarina species embed themselves in lemur fur, and likely did the aforementioned with subfossil lemurs. Seed dispersal biology is known for very few species in the spiny wood, including genera of plants suspected of depending on giant lemurs, such as Adansonia, Cedrelopsis, Commiphora, Delonix, Diospyros, Grewia, Pachypodium, Salvadora, Strychnos, and Tamarindus. For case, Delonix has edible pods that are rich in poly peptide, and Adansonia fruits have a nutritious pulp and large seeds that may accept been dispersed by Archaeolemur majori or Pachylemur insignis.[25]

Seed size may be a limiting cistron for some plant species, since their seeds are too large for living (extant) lemurs. The common chocolate-brown lemur (Eulemur fulvus) can consume seeds 20 mm (0.79 in) in diameter, while the black-and-white ruffed lemur (Varecia variegata) is capable of swallowing seeds up to 30 mm (one.ii in) in diameter. A large lemur, such as Pachylemur, which was more than twice the size of today's ruffed lemurs, could probably swallow even larger seeds. Seed dispersal limitations tied to megafaunal extinction are exhibited by Commiphora guillaminii. At present, this tree species has a short dispersal altitude, but its genetics indicate higher levels of regional cistron flow in the past, based on comparisons with a closely related species in Africa whose seeds are even so dispersed by large animals.[25]

Discovery and research [edit]

The writings of French colonial governor Étienne de Flacourt in the mid-17th century introduced the existence of behemothic Malagasy mammals to Western science with recorded eye-witness accounts from the local people of dangerous animals, hornless "water cows", and a large lemur-similar creature referred to locally as the tretretretre or tratratratra .[26] [28] Today, the latter is thought to accept been a species of Palaeopropithecus [17] or mayhap Megaladapis.[28] Flacourt described it as:

An animal every bit big equally a two-year-old dogie, with a round caput and a human face: the forepart feet are monkeylike, and the rear ones every bit well. Information technology has frizzy hair, a curt tail, and humanlike ears. ... I has been seen near Lake Lipomami, around which it lives. Information technology is a very solitary animal; the local people fear it greatly and flee from it as it does from them.

Early depictions of subfossil lemurs, such as this one of Megaladapis madagascariensis (top) from 1902, were based on inaccurate reconstructions due to confused pairing of skeletal remains. Modern reconstructions, such as this one of Thou. edwardsi (bottom), are much more accurate.

Local tales of a vocal'aomby (Malagasy for 'moo-cow that is not a cow'), or pygmy hippopotamus, led French naturalist Alfred Grandidier to follow a village headman to a marsh in southwestern Madagascar, a site called Ambolisatra, which became the starting time known subfossil site in Madagascar. In 1868, Grandidier uncovered the outset subfossil remains of lemurs—a humerus from Palaeopropithecus and a tibia of a sifaka. The Palaeopropithecus remains were not described for several decades, and it took decades more for the remains to be correctly paired with other sloth lemur remains.[26] It was not until 1893 that giant lemur species were formally described, when Charles Immanuel Forsyth Major discovered and described a long, narrow skull of Megaladapis madagascariensis in a marsh.[15] His discoveries in diverse marshes of central and southwestern Madagascar sparked paleontological interest,[12] resulting in an overabundance of taxonomic names and confused assemblages of bones from numerous species, including non-primates. Specimens were distributed between European museums and Madagascar, often resulting in the loss of field data that went with the specimens, if the information had been recorded at all.[15]

In 1905, Alfred Grandidier's son, Guillaume Grandidier, reviewed subfossil lemur taxonomy and determined that besides many names had been created. His review established most of the presently known family unit and genera names for the extinct lemurs.[12] Despite the taxonomic description, subfossil postcrania from unlike genera, peculiarly Megaladapis, Palaeopropithecus and Hadropithecus, continued to be incorrectly paired and sometimes assigned to non-primates.[15] Since subfossil remains were often dredged from marshes one by one, pairing skulls with other basic was often guesswork based on size-matching, and was not very accurate as a issue.[12] Even as late as the 1950s, bones of non-primates were attributed to subfossil lemurs.[15] One reconstruction of the confounded subfossil remains past paleontologist Herbert F. Standing depicted Palaeopropithecus as an aquatic fauna that swam near the surface, keeping its optics, ears, and nostrils slightly above h2o. Postcranial remains of Palaeopropithecus had previously been paired with Megaladapis by Guillaume Grandidier, who viewed information technology as a giant tree sloth, which he named Bradytherium. Continuing's aquatic theory was supported by Italian paleontologist Giuseppe Sera, who reconstructed Palaeopropithecus as an "arboreal-aquatic acrobat" that non only swam in water but climbed trees and dove from there into the water. Sera took the aquatic theory further in 1938 by including other extinct lemurs, including Megaladapis, which he viewed equally a thin ray-like swimmer that fed on mollusks and crustaceans while concealed underwater. It was primarily the paleontologist Charles Lamberton who correctly paired many of the confused subfossils, although others had also helped accost problems of association and taxonomic synonyms. Lamberton also refuted Guillaume Grandidier'south sloth theory for Megaladapis, besides as the aquatic lemur theory of Standing and Sera.[26]

Excavations during the early on 20th century past researchers similar Lamberton failed to unearth any new extinct lemur genera.[12] Fourteen of the approximately seventeen known species had previously been identified from field piece of work in southern, western, and central Madagascar.[15] When paleontological field piece of work resumed in the early on 1980s, new finds provided associated skeletal remains, including rare bones such as carpal bones (wrist basic), phalanges (finger and toe basic), and bacula (penile os). In some cases, nearly complete hands and feet were found.[12] [xv] Plenty remains have been found for some groups to demonstrate the concrete development of juveniles. Standard long-bone indices have been calculated in order to determine the intermembral alphabetize (a ratio that compares limb proportions), and body mass estimates have been fabricated based on long-bone circumference measurements. Fifty-fifty preserved fecal pellets from Archaeolemur have been found, allowing researchers to learn about its diet. More recently, electron microscopy has allowed researchers to study behavioral patterns, and Dna amplification has helped with genetic tests that determine the phylogenetic relationships between the extinct and living lemurs.[xv]

A new genus of sloth lemur, Babakotia, was discovered in 1986 by a team led by Elwyn Fifty. Simons of Duke University in karst caves on the Ankarana Massif in northern Madagascar.[12] Forth with Babakotia, a new species of Mesopropithecus, 1000. dolichobrachion, was besides discovered, but not formally described until 1995.[29] The aforementioned squad has likewise helped promote new ideas almost sloth lemur adaptations and the relationships among the four genera. They take also provided evidence that living species, such equally the indri and the greater bamboo lemur, have lost much of their original range.[12] In 2009, a new species of large sloth lemur, called Palaeopropithecus kelyus, was described from northwestern Republic of madagascar by a Franco-Madagascan team. The new species was found to be smaller than the 2 previously known species from the genus, and its diet reportedly consisted of more hard-textured nutrient.[30] The resurgence in subfossil lemur work has as well sparked new interest in Madagascar's small mammals, which have as well been found at the subfossil sites. This has led to new ideas well-nigh the origins, variety, and distribution of these animals.[31]

The number of Malagasy subfossil sites containing subfossil lemurs has increased significantly since the mid-20th century. At that time, subfossil lemurs had only been establish in the center, due south, and southwest of the island.[12] Since then, only the eastern rainforests accept not been represented, and paleodistributions are at present known for both extinct and living species effectually most of the isle.[6] [12] Big quantities of subfossil lemur remains have been found in caves, marshes, and streambank sites in drier regions.[six] The subfossil sites are clustered together geographically and are recent in age, mostly dating between 2,500 and 1,000 years onetime, with a few spanning back into the last glaciation, which concluded 10,000 years ago.[12]

Extinction [edit]

At least 17 species of giant subfossil lemur vanished during the Holocene, with all or nearly extinctions happening subsequently the colonization of Republic of madagascar by humans around 2,000 years agone.[8] [32] [33] Madagascar's megafauna included not but giant lemurs, simply too elephant birds, giant tortoises, several species of Malagasy hippopotamuses, Cryptoprocta spelea (a "giant fossa"), big crocodiles (Voay robustus), and Plesiorycteropus, a unique excavation mammal, all of which died out during the aforementioned menses. Madagascar'south megafaunal extinctions were among the well-nigh severe for whatsoever continent or large island, with all endemic wildlife over 10 kg (22 lb) disappearing,[32] totaling approximately 25 species.[22] The about severely impacted lemurs were generally large and diurnal,[32] particularly the clade containing the living indriids and extinct sloth lemurs. Although but the indriids are alive today and represent only a small percentage of the living lemur species, this clade collectively independent the majority of the extinct behemothic lemur species.[6] [eight]

Radiocarbon dating of multiple subfossil specimens shows that the giant subfossil lemurs were present on the isle until afterward human inflow.[17] [34]

By region, the Central Highlands lost the greatest number of lemur species.[xv] Information technology has lost nearly all of its woodland habitat, only some lemur species withal survive in isolated forest patches. Lemur diversity is tightly linked with plant variety, which in turn decreases with increased forest fragmentation. In farthermost cases, treeless sites such as the boondocks of Ampasambazimba from the central region no longer support any of the lemur species represented in their subfossil record. Other locations no longer have giant subfossil lemurs, yet they nonetheless maintain forested habitat that could support them.[6] Even though the giant lemurs have disappeared from these locations, while the smaller species survive in the woods patches that remain, the subfossil remains signal that the living species used to be more widespread and coexisted with the extinct species. The Central Highlands saw the greatest species loss, merely was not the only region or habitat type to witness extinctions. The to the lowest degree-understood region is the eastern rainforests, which have not yielded subfossil lemur remains. Consequently, it is impossible to know what percentage of lemur taxa were recently lost there; studies of Malagasy community (ethnohistory) along with archaeological testify suggests the eastern rainforests were more ecologically disturbed in the past than they are today. Hunting and trapping by humans may accept severely impacted large lemurs in this region every bit well.[15]

Comparisons of species counts from subfossil deposits and remnant populations in neighboring Special Reserves has further demonstrated decreased diversity in lemur communities and contracted geographic ranges. At Ampasambazimba in fundamental Republic of madagascar, 20 species of subfossil lemur have been establish. At nearby Ambohitantely Reserve, but 20% of those species even so survive. Just six of xiii species found at Ankilitelo and Ankomaka Caves in the southwest still survive at Beza Mahafaly Reserve. In the extreme n, the caves of Ankarana have yielded xix species, yet only ix remain in the surrounding forests. In the northwest, 10 or 11 subfossil species have been found at Anjohibe, whereas just six species remain at nearby Ankarafantsika National Park.[15]

As with the extinctions that occurred on other state masses during the late Pleistocene and Holocene (known equally the Fourth extinction event), the disappearance of Madagascar'south megafauna is tightly linked with the inflow of humans, with most all extinctions dating to around the aforementioned time of the earliest prove of human activity on the isle or significantly later.[8] [22] [35] The exact date of human being inflow is unknown; a radius (arm bone) of a Palaeopropithecus ingens with singled-out cut marks from the removal of flesh with sharp objects dates to 2325 ± 43 BP (2366–2315 cal year BP). Based on this testify from Taolambiby in the southwest interior, also as other dates for human-modified dwarf hippo bones and introduced plant pollen from other parts of the island, the arrival of humans is conservatively estimated at 350 BCE.[34] Measurements of stratigraphic charcoal and the appearance of exotic found pollen dated from Holocene core samples confirm these approximated dates for human inflow in the southwestern corner of the island and further advise that the central and northern parts of the island did not experience significant human bear on until 700 to 1,500 years later.[22] The humid forests of the lower interior of the island were the final to exist settled (as shown by the presence of charcoal particles), possibly due to the prevalence of human diseases, such as plague, malaria, and dysentery.[34] The unabridged island was not fully colonized by humans until the kickoff of the second millennium CE.[36]

The extinction of Madagascar's megafauna, including the behemothic lemurs, was one of the nearly contempo in history,[17] with large lemur species like Palaeopropithecus ingens surviving until approximately 500 years ago[37] and one bone of the extinct Hippopotamus laloumena radiocarbon dated to nearly 100 years BP.[34] An even wider extinction window for the subfossil lemurs, ranging upwardly until the 20th century, may be possible if reports of unidentified animals are true.[22] As recently as the early 17th century, dwindling populations of subfossil lemurs may take persisted in littoral regions where tree-cut and uncontrolled fires had less of an bear on. By that date, the Cardinal Highlands' forests were mostly gone, with the exception of scattered wood fragments and strips.[15] Forth the northwest declension, forms such as Archaeolemur may accept survived for more than a millennium later the arrival of humans.[38] This is supported by radiocarbon dates for Archaeolemur from the Ankarana Massif dating to 975 ± fifty CE[22] equally well as archaeological information that prove there was little human activity in the area until a few centuries ago, with low human being population density along the northwest coast until nearly 1500 CE.[38]

Hypotheses [edit]

In the 20th century, half dozen hypotheses for explaining the extinction of the giant subfossil lemurs have been proposed and tested. They are known equally the "Great Fire", "Smashing Drought", "Blitzkrieg", "Biological Invasion", "Hypervirulent Disease", and "Synergy" hypotheses.[fifteen] [34] [39] The first was proposed in 1927 when Henri Humbert and other botanists working in Republic of madagascar suspected that human-introduced fire and uncontrolled burning intended to create pasture and fields for crops transformed the habitats quickly across the island.[15] [34] [40] In 1972, Mahé and Sourdat proposed that the arid s had become progressively drier, slowly killing off lemur fauna as the climate changed.[15] [34] [41] Paul S. Martin practical his overkill hypothesis or "blitzkrieg" model to explain the loss of the Malagasy megafauna in 1984, predicting a rapid die-off as humans spread in a wave across the island, hunting the big species to extinction.[15] [34] [42] That same twelvemonth, Robert Dewar speculated that introduced livestock outcompeted the endemic wild fauna in a moderately fast series of multiple waves across the island.[xv] [34] [43] In 1997, MacPhee and Marx speculated that a rapid spread of hypervirulent affliction might explain the die-offs that occurred after the advent of humans worldwide, including Republic of madagascar.[15] [34] [35] Finally, in 1999, David Burney proposed that the complete ready of human impacts worked together, in some cases along with natural climate change, and very slowly (i.east., on a time scale of centuries to millennia) brought about the demise of the giant subfossil lemurs and other recently extinct endemic wildlife.[xv] [34] [44]

Since all extinct lemurs were larger than the ones that currently survive, and the remaining big forests still support large populations of smaller lemurs, large size appears to have conveyed some singled-out disadvantages.[12] [45] Large-bodied animals require larger habitats in order to maintain viable populations, and are well-nigh strongly impacted past habitat loss and fragmentation.[half-dozen] [12] Large folivores typically accept slower reproductive rates, live in smaller groups, and have depression dispersal rates (vagility), making them especially vulnerable to habitat loss, hunting pressure, and possibly disease.[6] [12] [33] Large, slow-moving animals are frequently easier to hunt and provide a larger amount of food than smaller prey.[45] Leaf-eating, large-bodied slow climbers, and semiterrestrial seed predators and omnivores disappeared completely, suggesting an extinction pattern based on habitat use.[8]

Since the subfossil bones of extinct lemurs have been plant alongside the remains of highly arboreal living lemur species, nosotros know that much of Republic of madagascar had been covered in forest prior to the arrival of humans; the wood coverage of the high plateau region has been debated. Humbert and other botanists suggested that the key plateau had once been blanketed in forest, later to be destroyed by burn down for employ by humans. Contempo paleoenvironmental studies by Burney take shown that the grasslands of that region accept fluctuated over the course of millennia and were not entirely created by humans.[12] Similarly, the role humans played in the aridification of the south and southwest has been questioned, since natural drying of the climate started before human arrival.[12] [15] The marshes of the region (in which subfossil remains have been institute) take stale up, subfossil sites take yielded a host of arboreal lemurs, and site names, such every bit Ankilitelo ('identify of iii kily or tamarind trees') suggest a recent wetter past.[xv] Pollen studies have shown that the aridification process began nigh 3,000 years ago, and peaked 1,000 years prior to the time of the extinctions. No extinctions occurred prior to the arrival of humans, and the recent climatic changes have not been equally severe as those prior to human arrival, suggesting that humans and their effect on the vegetation did play a office in the extinctions.[12] [22] [34] The central plateau lost more species than the dry out south and southwest, suggesting that degraded habitats were more affected than arid habitats.[15]

Over-hunting past humans has been one of the near widely accepted hypotheses for the ultimate demise of the subfossil lemurs.[37] The extinctions and human hunting pressure are associated due to the synchronicity of man inflow and species decline, equally well as the suspected naïveté of the Malagasy wildlife during the early encounters with human hunters. Despite the assumptions, bear witness of butchery has been minimal until recently, although folk memories of rituals associated with the killing of megafauna have been reported. Archeological evidence for butchery of giant subfossil lemurs, including Palaeopropithecus ingens and Pachylemur insignis, was constitute on specimens from two sites in southwestern Madagascar, Taolambiby and Tsirave. The bones had been collected in the early 20th century and lacked stratigraphic records; one of the bones with tool marks had been dated to the time of the first arrival of humans. Tool-induced os alterations, in the class of cuts and chop marks near joints and other feature cuts and fractures, indicated the early man settlers skinned, disarticulated, and filleted giant lemurs. Prior to these finds, only modified bones of dwarf hippos and elephant birds, every bit well as giant yep-aye teeth, had been found.[33]

Although at that place is evidence that habitat loss, hunting, and other factors played a role in the demise of the subfossil lemurs, prior to the synergy hypothesis, each had its own discrepancies. Humans may take hunted the giant lemurs for nutrient, but no signs of game-dependent abattoir accept been found. Madagascar was colonized by Iron-age pastoralists, horticulturalists, and fishermen, not large-game hunters. The blitzkrieg hypothesis predicts extinction inside 100 and 1,000 years as humans sweep beyond the isle,[22] [33] yet humans lived alongside the behemothic lemurs for more than 1,500 years. Alternatively, habitat loss and deforestation take been argued against because many behemothic lemurs were thought to be terrestrial, they are missing from undisturbed forested habitats, and their environment was non fully forested prior to the arrival of humans. Anthropologist Laurie Godfrey defended the effects of habitat loss by pointing out that nigh of the extinct lemurs have been shown to take been at least partly arboreal and dependent upon leaves and seeds for food, and also that these large-bodied specialists would be most vulnerable to habitat disturbance and fragmentation due to their low reproductive resilience and their demand for large, undisturbed habitats.[15] Still, much of the island remained covered in forest, even into the 20th century.[46]

Linking human being colonization to a specific cause for extinction has been hard since human activities accept varied from region to region.[46] No single human activity tin business relationship for the extinction of the giant subfossil lemurs, but humans are even so regarded as beingness primarily responsible. Each of the contributing human-caused factors played a role (having a synergistic consequence) in varying degrees.[17] [44] The most widespread and adaptable species, such every bit Archaeolemur, were able to survive despite hunting force per unit area and human-caused habitat change until man population growth and other factors reached a tipping point, cumulatively resulting in their extinction.[22]

Extinction timeline and the primary trigger [edit]

Hunting scene depicting a human (far left) and a sloth lemur (centre left) alongside 2 hunting dogs (right) from Andriamamelo Cave in western Madagascar

While it is generally agreed that both human and natural factors contributed to the subfossil lemur extinction, studies of sediment cores have helped to clarify the general timeline and initial sequence of events. Spores of the coprophilous mucus, Sporormiella, constitute in sediment cores experienced a dramatic decline before long after the arrival of humans. Since this fungus cannot complete its life cycle without dung from big animals, its decline also indicates a sharp decline in behemothic subfossil lemur populations, besides as other large herbivores, starting effectually 230–410 cal yr CE. Following the decline of megafauna, the presence of charcoal particles increased significantly, starting in the southwest corner of the island, gradually spreading to the other coasts and the island'south interior over the next 1,000 years.[34] The first evidence for the introduction of cattle to the island dates to i,000 years afterwards the initial reject of coprophilous fungal spores.[33]

The loss of grazers and browsers might have resulted in the accumulation of excessive institute material and litter, promoting more frequent and destructive wildfires, which would explain the rise in charcoal particles following the decline in coprophilous fungus spores.[34] This in plow resulted in ecological restructuring through the elimination of the wooded savannas and preferred arboreal habitats on which the giant subfossil lemurs depended. This left their populations at unsustainably low levels, and factors such as their slow reproduction, continued habitat degradation, increased contest with introduced species, and continued hunting (at lower levels, depending on the region) prevented them from recovering and gradually resulted in their extinction.[17]

Hunting is thought to take caused the initial rapid decline, referred to every bit the primary trigger, although other explanations may be plausible.[33] In theory, habitat loss should affect frugivores more than folivores, since leaves are more widely bachelor. Both big-bodied frugivores and big-bodied folivores disappeared simultaneously, while smaller species remained. Other large non-primate grazers also disappeared around the same time. Consequently, large body size has been shown to accept the strongest link to the extinctions—more than so than action patterns or diet. Since large animals are more than attractive as casualty, fungal spores associated with their dung declined apace with the arrival of humans, and abattoir marks have been found on giant subfossil lemur remains, hunting appears to be a plausible explanation for the initial pass up of the megafauna.[36]

Past region, studies have revealed specific details that have helped outline the serial of events that led to the extinction of the local megafauna. In the Central Highlands, dense forests existed until 1600 CE, with lingering patches persisting until the 19th and 20th centuries. Today, small-scale fragments stand up isolated among vast expanses of human being-created savanna, despite an average annual rainfall that is sufficient to sustain the evergreen forests once found at that place. Deliberately ready fires were the cause of the deforestation, and forest regrowth is restricted past soil erosion and the presence of burn-resistant, exotic grasses.[15] In the southeast, an extended drought dating to 950 cal twelvemonth BP led to fires and transition of open up grasslands. The drought may likewise accept pushed humans populations to rely more heavily on bushmeat. Had humans non been present, the subfossil lemur populations might take adjusted to the new weather and recovered. Had the drought not reduced the population of the subfossil lemurs, the pressure from the minor number of people living in the region at the fourth dimension might non have been plenty to crusade the extinctions.[37] All of the factors that have played a role in by extinctions are nevertheless nowadays and active today. As a outcome, the extinction event that claimed Republic of madagascar's giant subfossil lemurs is withal ongoing.[17]

Lingering populations and oral tradition [edit]

Recent radiocarbon dates from accelerator mass spectrometry fourteenC dating, such as 630 ± fifty BP for Megaladapis remains and 510 ± eighty BP for Palaeopropithecus remains, bespeak that the giant lemurs survived into mod times. Information technology is probable that memories of these creatures persist in the oral traditions of some Malagasy cultural groups. Some recent stories from around Belo sur Mer in southwestern Madagascar might even suggest that some of the giant subfossil lemurs still survive in remote forests.[47]

Flacourt'southward 1658 description of the tretretretre or tratratratra was the first mention of the now extinct behemothic lemurs in Western culture, just it is unclear if he saw it.[28] The creature Flacourt described has traditionally been interpreted as a species of Megaladapis. The size may have been exaggerated, and the "round caput and a human being face" would not match Megaladapis, which had an enlarged snout and the least frontward-facing eyes of all primates. The facial clarification, and the mention of a short tail, lone habits, and other traits better friction match the most contempo interpretation — Palaeopropithecus.[7] Malagasy tales recorded past the 19th-century folklorist Gabriel Ferrand describing a large creature with a flat homo-similar face that was unable to negotiate smooth rock outcrops also best lucifer Palaeopropithecus, which would also accept had difficulty on flat smoothen surfaces.[26]

In 1995, a enquiry team led by David Burney and Ramilisonina performed interviews in and effectually Belo sur Mer, including Ambararata and Antsira, to find subfossil megafaunal sites used early on in the century past other paleontologists. During carefully controlled interviews, the team recorded stories of recent sightings of dwarf hippos (called kilopilopitsofy ) and of a large lemur-like beast known as kidoky ; a report of the interviews was published in 1998 with encouragement from primatologist Alison Jolly and anthropologist Laurie Godfrey. In i interview, an 85-year-quondam man named Jean Noelson Pascou recounted seeing the rare kidoky upwards close in 1952. Pascou said that the animal looks similar to a sifaka, but had a human-like confront, and was "the size of a seven-year-one-time girl". It had night fur and a discernible white spot both on the brow and below the mouth. According to Pascou, it was a shy animal that fled on the ground instead of in the trees. Burney interpreted the quondam man as saying that it moved in "a series of leaps",[48] but Godfrey later claimed that "a series of bounds" was a better translation — a clarification that would closely friction match the human foot anatomy of monkey lemurs, such every bit Hadropithecus and Archaeolemur.[47] Pascou could as well imitate its call, a long single "whoop", and said that kidoky would come closer and go on calling if he imitated the call correctly. The phone call Pascou imitated was comparable to that of a curt telephone call for an indri, which lives on the other side of Republic of madagascar. When shown a moving picture of an indri, Pascou said kidoky did not look like that, and that information technology had a rounder face, more similar to a sifaka. Pascou also speculated that kidoky could stand on two legs and that information technology was a solitary animal.[48]

Another interviewee, François, a middle-aged woodcutter who spent time in the forests inland (eastward) from the main road between Morondava and Belo sur Mer, and 5 of his friends, reported seeing kidoky recently. Their description of the animal and François's simulated of its long call were virtually identical to Pascou's. One of the young men insisted that its fur had a lot of white in it, merely the other men could not confirm that. François and his friends reported that it had never climbed a tree in their presence, and that it flees on the ground in brusque leaps or bounds. When Burney imitated the sideways leaping of a sifaka moving on the ground, i of the men corrected him, pointing out that he was imitating a sifaka. The human being'due south imitation of the gallop kidoky used was very baboon-like. The men also reported that imitating its call can describe the fauna closer and cause it to continue calling.[48]

Burney and Ramilisonina admitted that the most parsimonious caption for the sightings was that kidoky was a misidentified sifaka or other larger living lemur species. The authors did not feel comfortable with such a dismissal considering of their careful quizzing and utilise of unlabeled colour plates during the interviews and because of the competence demonstrated by the interviewees in regards to local wild fauna and lemur habits. The possibility of a wild introduced baboon surviving in the forests could not exist dismissed. The descriptions of kidoky , with its terrestrial baboon-like gait, brand Hadropithecus and Archaeolemur the near plausible candidates amidst the giant subfossil lemurs. At the very least, the stories support a wider extinction window for the giant subfossil lemurs, suggesting that their extinction was recent plenty for such bright stories to survive in the oral traditions of the Malagasy people.[48]

See too [edit]

References [edit]

- ^ a b c Sussman 2003, pp. 107–148.

- ^ Mittermeier et al. 2006, p. 325.

- ^ Jungers, Demes & Godfrey 2008, pp. 343–360.

- ^ a b Godfrey, Jungers & Burney 2010, p. 356.

- ^ Sussman 2003, pp. 257–269.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l thousand n o p q r s Godfrey et al. 1997, pp. 218–256.

- ^ a b c d Simons 1997, pp. 142–166.

- ^ a b c d east f 1000 h i j k l m n o p q r due south t u five west x y z aa ab Godfrey & Jungers 2003, pp. 1247–1252.

- ^ Godfrey, L. R.; Sutherland, Yard. R.; Paine, R. R.; Williams, F. L.; Male child, D. S.; Vuillaume-Randriamanantena, M. (1995). "Limb joint surface areas and their ratios in Malagasy lemurs and other mammals". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 97 (ane): 11–36. doi:ten.1002/ajpa.1330970103. PMID 7645671.

- ^ Walker, A.; Ryan, T. Chiliad.; Silcox, M. T.; Simons, E. L.; Spoor, F. (2008). "The semicircular canal organisation and locomotion: the case of extinct lemuroids and lorisoids". Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews. 17 (3): 135–145. doi:10.1002/evan.20165. S2CID 83737480.

- ^ a b c d e f one thousand h i j k l m due north o p q r s t u v w 10 y z aa Mittermeier et al. 2006, pp. 37–51.

- ^ Jungers, W. L.; Godfrey, L. R.; Simons, East. L.; Chatrath, P. Due south. (1997). "Phalangeal curvature and positional behavior in extinct sloth lemurs (Primates, Palaeopropithecidae)" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 94 (22): 11998–12001. Bibcode:1997PNAS...9411998J. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.22.11998. PMC23681. PMID 11038588.

- ^ a b c Rafferty, Grand. L.; Teaford, M. F.; Jungers, W. L. (2002). "Tooth microwear of subfossil lemurs: improving the resolution of dietary inferences" (PDF). Journal of Man Evolution. 43 (five): 645–657. doi:x.1006/jhev.2002.0592. PMID 12457853. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-16.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j m l thou n o p q r s t u 5 due west 10 y Godfrey & Jungers 2002, pp. 97–121.

- ^ King, S. J.; Godfrey, L. R.; Simons, East. L. (2001). "Adaptive and phylogenetic significance of ontogenetic sequences in Archaeolemur, subfossil lemur from Madagascar". Journal of Homo Development. 41 (6): 545–576. doi:10.1006/jhev.2001.0509. PMID 11782109.

- ^ a b c d e f m h i j one thousand l Godfrey, Jungers & Burney 2010, Affiliate 21.

- ^ Horvath, J. E.; Weisrock, D. Due west.; Embry, S. 50.; Fiorentino, I.; Balhoff, J. P.; Kappeler, P.; Wray, G. A.; Willard, H. F.; Yoder, A. D. (2008). "Development and application of a phylogenomic toolkit: Resolving the evolutionary history of Republic of madagascar's lemurs" (PDF). Genome Inquiry. eighteen (three): 489–499. doi:x.1101/gr.7265208. PMC2259113. PMID 18245770.

- ^ Orlando, L.; Calvignac, South.; Schnebelen, C.; Douady, C. J.; Godfrey, L. R.; Hänni, C. (2008). "Dna from extinct behemothic lemurs links archaeolemurids to extant indriids". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 8 (121): 121. doi:ten.1186/1471-2148-8-121. PMC2386821. PMID 18442367.

- ^ a b c Jungers, W. L.; Godfrey, L. R.; Simons, E. Fifty.; Chatrath, P. Southward. (1995). "Subfossil Indri indri from the Ankarana Massif of northern Republic of madagascar". American Periodical of Physical Anthropology. 97 (4): 357–366. doi:ten.1002/ajpa.1330970403. PMID 7485433.

- ^ a b Mittermeier et al. 2006, p. 235.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Simons, E. 50.; Burney, D. A.; Chatrath, P. Southward.; Godfrey, L. R.; Jungers, W. L.; Rakotosamimanana, B. (1995). "AMS xivC Dates for Extinct Lemurs from Caves in the Ankarana Massif, Northern Republic of madagascar". Quaternary Research. 43 (2): 249–254. Bibcode:1995QuRes..43..249S. doi:10.1006/qres.1995.1025.

- ^ a b Muldoon, Chiliad. M.; Simons, Eastward. L. (2007). "Ecogeographic size variation in pocket-sized-bodied subfossil primates from Ankilitelo, Southwestern Madagascar". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 134 (2): 152–161. doi:ten.1002/ajpa.20651. PMID 17568444.

- ^ Beck, R. One thousand. D. (2009). "Was the Oligo-Miocene Australian metatherian Yalkaparidon a 'mammalian woodpecker'?". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 97 (i): 1–17. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2009.01171.x.

- ^ a b c d e f Crowley, B. E.; Godfrey, L. R.; Irwin, Thousand. T. (2011). "A glance to the by: subfossils, stable isotopes, seed dispersal, and lemur species loss in Southern Madagascar". American Periodical of Primatology. 73 (i): 25–37. doi:10.1002/ajp.20817. PMID 20205184. S2CID 25469045.

- ^ a b c d e Godfrey, L. R.; Jungers, Westward. L. (2003). "The extinct sloth lemurs of Madagascar" (PDF). Evolutionary Anthropology: Bug, News, and Reviews. 12 (6): 252–263. doi:10.1002/evan.10123. S2CID 4834725. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 Jan 2011.

- ^ Godfrey, L. R.; Sutherland, M. R.; Petto, A. J.; Boy, D. Due south. (1990). "Size, infinite, and adaptation in some subfossil lemurs from Madagascar". American Journal of Concrete Anthropology. 81 (1): 45–66. doi:x.1002/ajpa.1330810107. PMID 2301557.

- ^ a b c d Mittermeier et al. 2006, p. 29.

- ^ Simons, E. L.; Godfrey, L. R.; Jungers, W. L.; Chatrath, P. S.; Ravaoarisoa, J. (1995). "A new species of Mesopropithecus (Primates, Palaeopropithecidae) from Northern Madagascar". International Journal of Primatology. 15 (5): 653–682. doi:ten.1007/BF02735287. S2CID 21431569.

- ^ Gommery, D.; Ramanivosoa, B.; Tombomiadana-Raveloson, Southward.; Randrianantenaina, H.; Kerloc'h, P. (2009). "A new species of giant subfossil lemur from the North-West of Republic of madagascar (Palaeopropithecus kelyus, Primates)". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 8 (5): 471–480. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2009.02.001.

- "New Extinct Lemur Species Discovered In Madagascar". ScienceDaily (Press release). 27 May 2009.

- ^ Goodman, South. M.; Vasey, North.; Burney, D. A. (2007). "Clarification of a new species of subfossil shrew tenrec (Afrosoricida: Tenrecidae: Microgale) from cave deposits in southeastern Madagascar" (PDF). Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington. 120 (iv): 367–376. doi:10.2988/0006-324X(2007)120[367:DOANSO]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ a b c Sussman 2003, pp. 149–229.

- ^ a b c d due east f Perez, V. R.; Godfrey, L. R.; Nowak-Kemp, Grand.; Burney, D. A.; Ratsimbazafy, J.; Vasey, Due north. (2005). "Prove of early on butchery of giant lemurs in Madagascar". Journal of Man Evolution. 49 (half-dozen): 722–742. doi:x.1016/j.jhevol.2005.08.004. PMID 16225904.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j 1000 l m n Burney, D. A.; Burney, Fifty. P.; Godfrey, L. R.; Jungers, W. L.; Goodman, South. Chiliad.; Wright, H. T.; Jull, A. J. T. (July 2004). "A chronology for late prehistoric Madagascar". Journal of Human Evolution. 47 (ane–ii): 25–63. doi:x.1016/j.jhevol.2004.05.005. PMID 15288523.

- ^ a b MacPhee & Marx 1997, pp. 169–217.

- ^ a b Godfrey, L. R.; Irwin, 1000. T. (2007). "The Evolution of Extinction Hazard: Past and Nowadays Anthropogenic Impacts on the Primate Communities of Madagascar". Folia Primatologica. 78 (5–half dozen): 405–419. doi:10.1159/000105152. PMID 17855790. S2CID 44848516.

- ^ a b c Virah-Sawmy, M.; Willis, K. J.; Gillson, 50. (2010). "Evidence for drought and forest declines during the contempo megafaunal extinctions in Madagascar". Periodical of Biogeography. 37 (3): 506–519. doi:x.1111/j.1365-2699.2009.02203.10.

- ^ a b Burney, D. A.; James, H. F.; Grady, F. Five.; Rafamantanantsoa, J. G.; Ramilisonina; Wright, H. T.; Cowart, J. (1997). "Environmental alter, extinction and human being activity: evidence from caves in NW Madagascar". Journal of Biogeography. 24 (6): 755–767. doi:ten.1046/j.1365-2699.1997.00146.10. hdl:2027.42/75139.

- ^ Burney, D.A.; Jungers, William L. (2003). "Box 5. Extinction in Republic of madagascar: The Anatomy of a Catastrophe". Evolutionary Anthropology: Bug, News, and Reviews. 12 (half dozen): 261. doi:ten.1002/evan.10123. S2CID 4834725. in Godfrey et al., "The extinct sloth lemurs of Republic of madagascar", Evolutionary Anthropology 12:252–263.

- ^ Humbert, H. (1927). "Destruction d'une flore insulaire par le feu". Mémoires de fifty'Académie Malgache (in French). 5: 1–fourscore.

- ^ Mahé, J.; Sourdat, M. (1972). "Sur l'extinction des vertébrés subfossiles et l'aridification du climat dans le Sud-Ouest de Madagascar" (PDF). Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France (in French). xiv: 295–309. doi:10.2113/gssgfbull.S7-XIV.1-5.295.

- ^ Martin 1984, pp. 354–403.

- ^ Dewar 1984, pp. 574–593.

- ^ a b Burney 1999, pp. 145–164.

- ^ a b Preston-Mafham 1991, pp. 141–188.

- ^ a b Dewar 2003, pp. 119–122.

- ^ a b Goodman, Ganzhorn & Rakotondravony 2003, pp. 1159–1186.

- ^ a b c d Burney, D. A.; Ramilisonina (1998). "The Kilopilopitsofy, Kidoky, and Bokyboky: Accounts of Strange Animals from Belo-sur-mer, Madagascar, and the Megafaunal "Extinction Window"". American Anthropologist. 100 (4): 957–966. doi:10.1525/aa.1998.100.iv.957. JSTOR 681820.

- Books cited

- Burney, D.A. (1999). "Chapter 7: Rates, patterns, and processes of landscape transformation and extinction in Madagascar". In MacPhee, R.D.E.; Sues, H.-D. (eds.). Extinctions in Virtually Time. Springer. pp. 145–164. doi:10.1007/978-one-4757-5202-1_7. ISBN978-0-306-46092-0.

- Goodman, S.M.; Benstead, J.P., eds. (2003). The Natural History of Madagascar. Academy of Chicago Press. ISBN0-226-30306-3.

- Dewar, R. Eastward. (2003). Relationship between Homo Ecological Pressure and the Vertebrate Extinctions. pp. 119–122.

- Goodman, S.M.; Ganzhorn, J.U.; Rakotondravony, D. (2003). Introduction to the Mammals. pp. 1159–1186.

- Godfrey, L.R.; Jungers, W.Fifty. (2003). Subfossil Lemurs. pp. 1247–1252.

- Goodman, S.Chiliad.; Patterson, B.D., eds. (1997). Natural Change and Human being Impact in Madagascar. Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN978-ane-56098-682-ix.

- Simons, E.L. (1997). Chapter half-dozen: Lemurs: Erstwhile and New. pp. 142–166.

- MacPhee, R.D.Due east.; Marx, P.A. (1997). Chapter 7: The twoscore,000-year plague: humans, hypervirulent diseases, and first-contact extinctions. pp. 169–217.

- Godfrey, L.R.; Jungers, W.L.; Reed, M.E.; Simons, E.L.; Chatrath, P.S. (1997). Chapter eight: Subfossil Lemurs. pp. 218–256.

- Godfrey, L.R.; Jungers, W.L.; Burney, D.A. (2010). "Affiliate 21: Subfossil Lemurs of Madagascar". In Werdelin, Fifty.; Sanders, W.J (eds.). Cenozoic Mammals of Africa. University of California Press. pp. 351–367. ISBN978-0-520-25721-4.

- Godfrey, L.R.; Jungers, Westward.L. (2002). "Affiliate 7: Quaternary fossil lemurs". In Hartwig, Due west.C. (ed.). The Primate Fossil Record. Cambridge University Press. pp. 97–121. ISBN0-521-66315-six.

- Jungers, West.Fifty.; Demes, B.; Godfrey, L.R. (2008). "How Big were the "Giant" Extinct Lemurs of Madagascar?". In Fleagle, J.M.; Gilbert, C.C. (eds.). Elwyn Simons: A Search for Origins. Springer. pp. 343–360. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-73896-3_23. ISBN978-0-387-73895-half dozen.

- Martin, P.S.; Klein, R.G., eds. (1984). Fourth Extinctions: A Prehistoric Revolution. University of Arizona Printing. ISBN978-0-8165-0812-9.

- Martin, P.Due south. (1984). Prehistoric overkill: the global model. pp. 354–403. ISBN9780816511006.

- Dewar, R. (1984). Extinctions in Madagascar: the loss of the subfossil fauna. pp. 574–593.

- Mittermeier, R.A.; Konstant, W.R.; Hawkins, F.; Louis, Due east.E.; et al. (2006). Lemurs of Madagascar. Illustrated by S.D. Nash (2nd ed.). Conservation International. ISBNone-881173-88-7. OCLC 883321520.

- Preston-Mafham, K. (1991). Republic of madagascar: A Natural History. Facts on File. ISBN978-0-8160-2403-two.

- Sussman, R.W. (2003). Primate Ecology and Social Structure. Pearson Custom Publishing. ISBN978-0-536-74363-3.

External links [edit]

-

Media related to Category:Subfossil lemurs at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Category:Subfossil lemurs at Wikimedia Commons

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Subfossil_lemur

Posted by: labordebuirl1989.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Is The Most Recently Extinct Animal"

Post a Comment